In an earlier post in this series I discussed business issues and opportunities related to a potential launch by Comcast of a WiFi-based service that could:

- further monetize the company’s investments in millions of in-home dual-SSID WiFi gateway devices;

- provide it with a relatively low-cost, high-margin entry into the wireless market space;

- give it a powerful position in the emerging market for nomadic, multiscreen multimedia services and;

- strengthen its overall market power in the communication sector as a whole.

In this two-part post I’m considering this same topic, but from a public policy perspective.

Viewed in very broad strokes, we have on one hand the potential benefits from what could be a new and attractively priced competitive option in the wireless sector. On the other hand, we have a range of complex and intertwined public policy issues related to the continued expansion of Comcast’s market power across multiple sectors of the communications industry, and the prospects for anti-competitive impacts of that expansion.

In Part 1 I focused on Comcast’s use of dual-SSID in-home gateways to deploy a network of millions of public access hotspots while: 1) charging customers $10 per month to lease these dual-use devices, which also provide them with a private in-home WiFi network; 2) using these customers’ electricity to power gateway devices that are also used as public-access hotspots; 3) activating the gateway’s public hotspot capability with an opt-out (vs. an opt-in) approach that has been criticized as “difficult to use or broken.”

Here in Part 2 I’m going to consider the competitive and public interest impacts of this strategy in the broader context of Comcast’s unique and synergistic mix of market power.

Who controls our “window on the world?”

As suggested in an earlier post, one emerging and important arena for competition is services that make it easier for customers to manage their media consumption across multiple fixed and portable devices, including large screen TVs, computer monitors, tablets and smartphones.

As the dominant provider of both wireline Internet access and traditional multichannel video, Comcast is well positioned to expand the scope of that dominance into this emerging “nomadic multiscreen multimedia” market. This is especially true if it can successfully integrate wireless connectivity and provide customers with a combination of connectivity, content and user-interface that can’t be matched by other companies that lack Comcast’s broad set of competitive tools and assets.

As public comments by Comcast executives have suggested, the company’s deployment of more than 8 million WiFi hotspots is a big step toward achieving the threshold level of wireless connectivity needed to support this kind of strategy (as discussed in an earlier post, ubiquitous coverage and seamless handoff capabilities are less necessary for this type of “nomadic” service).

The multisource, multiscreen user interface arena has attracted a range of large and small companies from related sectors, including tech giants like Apple, Google, Amazon and Sony, as well as Dish Network’s Sling TV, smaller players like Roku, and online content distributors like Netflix and Hulu. But, so far, none has been able to achieve a position as the dominant gateway to the widening world of online media (this recent Wall Street Journal article provides some perspective on the challenges in this arena for both companies and consumers).

Can Apple become “the new Comcast for the Internet?”

With Apple once again in negotiations with major TV content providers, the Washington Post’s Cecilia Kang raises the question of whether the creator of the iPod, iTunes, iPhone and iPad, which fundamentally transformed the music and mobile communications industries, might finally be ready to work similar magic in the TV business.

Television viewers have long yearned for the day they could get their favorite programs streamed online without having to pay a huge cable bill each month. That day has arrived — and it’s confusing…

Enter one big company — Apple — that wants to clear up all the confusion. If it succeeds, Apple could become the biggest gateway to online video — the new Comcast for the Internet. And it has more cash on hand than any of its rivals to secure the most-desired shows.

As others have done before, Kang is speculating that perhaps Apple’s expertise in user interface and product design, coupled with its extremely deep pockets, passionate user base and experience transforming other media and communication industries, may finally be a powerful enough combination to enable the company to become “the new Comcast for the Internet.”

In a Backchannel column, Harvard professor Susan Crawford expresses a different view of this issue, suggesting that, if regulators are not proactive, Comcast itself may become an even more dominant version of “the Comcast for the Internet.”

In considering the possibilities, it’s worth noting that Apple is wildly popular among its large and expanding user base, while Comcast is regularly rated among the nation’s most unpopular companies in customer satisfaction surveys. But it’s also important to keep in mind that Comcast has a very strong market position in both content creation and distribution, both in traditional cable and broadcast television, as well as Internet access.

It’s also worth looking back at Apple’s previous successes as a market disruptor. For example, in the music industry record companies, as content owners, had long dominated traditional forms of content distribution. But (unlike Comcast), they had no direct involvement in the Internet access market and, in fact, tended to strongly (and some would say foolishly) resist the prospect of online distribution of the content they’d long controlled. As a result, when Apple was preparing to launch its iTunes/iPod music strategy, the record companies were fighting an increasingly painful, costly and desperate battle against online piracy–a battle they seemed destined to lose unless they adopted a fundamentally different strategy. That situation provided a large and very ripe opportunity for Apple, which it very skillfully exploited.

Cellular carriers come from the other end of the value chain. Their core business is connectivity, not content. And though they have exerted (and continue to exert) considerable influence over the introduction of devices, features and applications, their efforts to control how these evolve have faced mounting pressure from customers, device makers, regulators and a growing assortment of application and content providers.

And, importantly, cellular carriers have faced a greater degree of competition among themselves than is typically found in the wireline access market. As discussed below, this difference is important to keep in mind when looking to Apple’s disruption of the mobile communications market for lessons about the company’s ability to achieve something comparable in the video market.

In the mobile communication space we have four national carriers (and a range of MVNO retailers and more localized providers) competing against each other. At the top of the market-power pyramid are two fairly equally matched giants (AT&T and Verizon) vying for the #1 market position. In the tier below them are T-Mobile and Sprint which (especially after receiving significant new injections of financing and spectrum) attempt to gain competitive advantage via price cuts, innovation and aggressive marketing. Since this kind of strategy involves a significant amount of risk, T-Mobile and Sprint are also under considerable pressure from Wall Street to avoid the kind of missteps that can fuel a negative spiral of decline in what is a very capital-intensive and churn-sensitive business (most recently T-Mobile appears to be doing well on this front, while Sprint continues to struggle).

This competitive dynamic contributed to AT&T’s decision to cede an unprecedented level of control over the mobile device and application market to Apple, in exchange for five years of exclusive distribution rights to the iPhone. Though that decision cost AT&T a degree of control it has yet to reclaim, it strengthened the carrier’s market position relative to Verizon, especially in the then-emerging and strategically important smartphone sector. This, in turn, helped push Verizon to embrace Google’s Android initiative (even though this involved a comparable loss of carrier control), since it represented the best option for competing in the smartphone space during the five years in which AT&T had exclusive rights to sell the iPhone.

Comcast’s expansive market power a challenge, even for Apple

In contrast to either of these two earlier “Apple disruptions,” Comcast is a dominant player in both distribution and content:

1) It is, by a wide margin, the largest provider of traditional multichannel video and broadband Internet access (especially since the FCC redefined minimum broadband speeds);

2) Since its NBCU acquisition, it is one of the nation’s (and the world’s) largest providers of media content.

In considering the prospects for Apple to become “the new Comcast of the Internet,” it’s important to keep in mind that the wired access sector has no competitive dynamic comparable to what we see in the cellular market (e.g., two dominant and fairly equally matched national providers competing with each other and with two smaller national players, and a range of resellers and smaller providers focused on particular market segments (e.g., prepaid and/or selected geographic regions)).

In contrast to this wireless market competitive dynamic, what we find in the wireline access market is a clear trend of increased dominance by cable operators, who virtually never compete with each other. And, at the head of the cable pack is Comcast which, if regulators approve its plans, will grow even larger after acquiring Time Warner Cable, the cable industry’s second largest provider. The only significant exception to this cable dominance is the minority of local markets where Verizon or some other entity has deployed fiber optic networks (Verizon’s fiber coverage encompasses roughly 15% of the nation’s households).

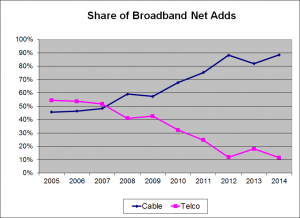

As the graph below illustrates, a decade ago the cable-telco battle for wireline broadband subscriber growth was pretty evenly contested, with telcos actually claiming more than half of net adds from 2005 through 2007. As the graph shows, however, cable’s share has risen dramatically since then, exceeding 80% during the past three years and close to 90% in two of these years. The graph is based on data compiled by the Leichtman Research Group, most of it based on data reported by publicly-traded companies. Since the Leichtman data includes Verizon’s fiber optic markets, where the telco remains a very strong local competitor, it seems reasonable to assume that the graph actually understates cable’s dominance in the rest of the country.

We can see a similar dynamic if we compare the broadband subscriber growth of Comcast, the nation’s largest cable operators, with that of AT&T, the largest wireline telco.

While both companies claimed just under 16 million broadband customers at the end of 2009 (15.9 mil. for Comcast, 15.8 mil. for AT&T), Comcast has grown dramatically faster since then. It ended 2014 with nearly 22 million broadband customers, compared to less than 16.5 million for AT&T (adjusting for a recent sale). According to the two companies’ financial reports, Comcast added nearly 1.3 million broadband customers in 2014, compared to just 19,000 for AT&T. And for the three year period ending in 2014, Comcast added nearly 3.8 million broadband customers (a 21% increase), versus just 17,000 net adds for AT&T (a 0.1% increase).

This competitive trend differs dramatically from what we’ve been seeing in the wireless sector since regulators blocked AT&T’s planned acquisition of T-Mobile in 2011. Three years following that decision, T-Mobile’s innovative and aggressive Un-carrier strategy has driven increased price competition and allowed the company in 2014 to outperform its larger peers on key measures of subscriber and revenue growth. While it could be argued that Google Fiber and/or municipal fiber networks are driving a similar level of competitive disruption in the wireline sector, the reality is that these remain limited to a very small number of local markets, whereas T-Mobile’s competitive impacts are a nationwide phenomenon.

The user interface: a key lever of market power

Another important difference worth noting here is that, unlike the mobile device market, the cable set-top box market has, for virtually its entire existence, been dominated by two vendors, Motorola and Cisco (formerly General Instrument and Scientific Atlanta). These vendors have, in turn, been pretty tightly controlled (in terms of both features and pricing) by the dominant cable providers.

In her column, Crawford stresses the importance of a new FCC-sponsored advisory group with the acronym DSTAC (which stands for Downloadable Security Technology Advisory Committee). The group’s charter, she explains, is to propose by September 2015 “a way for any consumer device to download a gateway that will provide secure access to any pay TV content — over the top or otherwise.” This, she notes, would allow “other companies [to] compete to provide a host of interfaces blending pay TV and over the top content across a host of devices.”

Drawing historical parallels dating back to the 1968 Carterphone decision, Crawford provides some context for understanding the significance of the DSTAC effort:

In 1996, Congress passed a law directing the FCC to ensure a competitive retail marketplace for consumer devices used to access cable and satellite pay TV services. That law, Section 629 of the Telecommunications Act, hasn’t brought about the changes Congress wanted. Today, you can choose among hundreds of wireless handsets and innumerable laptops and tablets. But when it comes to the vital category of set-top boxes—that ugly metal thing that plugs into your TV and talks to the wire coming into your house—you have very little choice.

Five years ago, the Obama administration’s National Broadband Plan pointed out that Motorola and Cisco controlled more than 90% of the set-top box market and strongly recommended that the FCC finally implement Section 629. Efforts along these lines then died a quiet death inside the agency. At the end of 2014, Congress passed a law that wipes out the FCC’s old rules on this subject as of September 15, 2015.

Should the DSTAC effort fail, Crawford suggests the following as a likely though unfortunate scenario.

What if all of the devices in your life had a common interface, controlled by a single company, that picked what video content you could easily search and access online? What if that single company had its own economic reasons to support some “channels” and hide others? Welcome to the world of Xfinity, Comcast’s brand name for its services. You’ve seen the advertising. Now here’s the big idea: If Comcast has its way, Xfinity will be Americans’ window on the world. Basically, our only window…

To get there, Comcast is licensing Xfinity for free to other cable distributors, set-top box makers, and computer-chip manufacturers, ensuring that its platform is widely adopted…The payoff for Comcast and its collaborators? They’ll be able to ensure that their own video on demand services are easy to find but users can’t search simultaneously across Vudu, Netflix, or YouTube. They’ll control video navigation and, thus, the user experience — and the profits that flow from it. Program guides, DVR recordings, and “pretty much everything but the volume control” on Xfinity-obedient devices will be governed from the cloud, according to Rob Rockell, Vice President of Engineering for Comcast. This is a very big deal.

Consumers aren’t the only interested parties that will feel the squeeze of Xfinity. Last April, Comcast bought FreeWheel Media, a TV advertising company that “personalizes and inserts online video ads for media clients,” according to Reuters. Because FreeWheel’s clients include media conglomerates 21st Century Fox, Disney, Time Warner, and Viacom, Comcast (which owns its own competing media conglomerate, NBCU) now knows everything about who watches what online; powerful ammunition in negotiating with programmers.

And it is not a coincidence that Time Warner Cable stopped negotiating with Apple TV when Comcast kicked off its merger efforts: TWC would have allowed its users to replace their set top boxes with an Apple TV. Comcast doesn’t offer a Roku app, doesn’t support Chromecast well, and generally isn’t interested in the idea that subscribers might migrate away from pay TV packages to over the top alternatives traveling over Comcast’s wires. As Comcast’s Executive Vice President David Cohen said in 2011, “We’re not very good partners. We like to run things.”

I agree with Crawford about the importance of keeping our “window on the world” (i.e., our access to the Internet) open via healthy-functioning markets in which end users can freely choose the devices, user interfaces, content and services that best serve their needs; and where suppliers of these various components of value are free to offer them to end users without needing approval from other companies, including those that own the access networks over which these transactions take place.

For those concerned with the technical aspects of keeping the Internet’s “window on the world” open, I recommend this video of DSTAC’s first meeting. Though long, it’s a good introduction to the advisory group’s mission, the companies and individuals participating in it, and the initial perspectives and priorities they bring to the negotiating table. A list of DSTAC members and their company affiliations is available here.

As I see it, a key goal of DSTAC—and communication policy in general—is to avoid the oxymoronic outcome of having ANY single company (or alliance between a few companies) become “the new Comcast for the Internet.”